|

What if we stole the bell before Hell Week? When a Basic Underwater Demolition/ SEAL (BUD/S) trainee has had enough, he is supposed to ring a bell to signal he’s quitting. More students drop out of training during Hell Week than any other time, but my class was determined not to lose a single classmate during the infamous week.

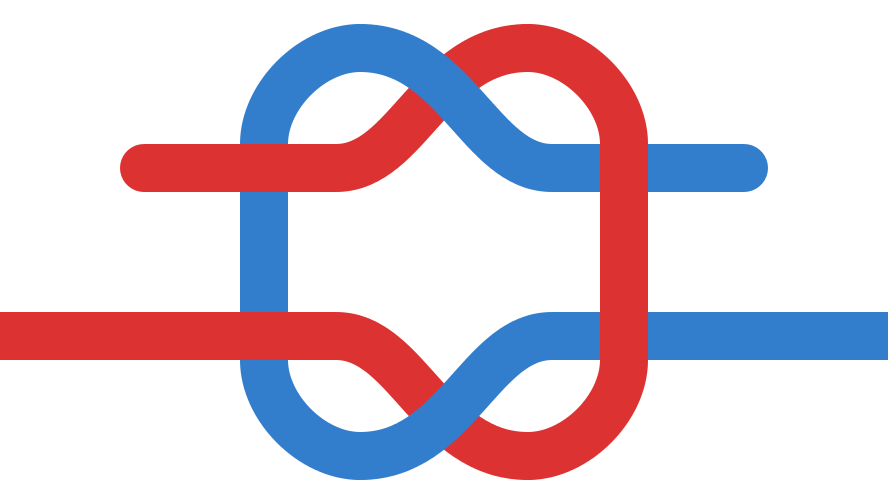

In our barracks on the beach of Coronado, California, our class met in the lounge, and we hatched a plan to steal the bell. We elected one of our ninjas to do the deed, and then he was to hand it off to the guy voted least likely to quit Hell Week, who would stash it somewhere and not tell a soul where it was. We were always looking for a competitive edge—playing the game in a way that favored us. It was important to think ahead as to what the consequences of such actions might be, but it was also important to play the game with guts. That evening, some of us slept while others remained awake in their beds. Wearing my Battle Dress Uniform (BDUs) and combat boots in preparation for Hell Week, I slept soundly in my rack. I awoke to the sound of a metal click in the head (restroom). My room was black, except for the sudden flash of an M60 machine gun blasting from inside the head. The noise assaulted my ears. I saw my classmates crawling out the door, so I crawled out with them. “Move, move, move!” an instructor yelled. Outside on the grinder (an asphalt area used for exercise, drills, and other activities), artillery simulators exploded in the night air—an incoming shriek followed by a boom. More machine guns rattled off, a fog machine pumped a blanket of mist over the ground, and green ChemLights decorated the outer perimeter. Then water hoses sprayed us as a swarm of instructors descended. An instructor blew his whistle. Tweet—whistle drill. We dove to the ground, crossed our legs, covered our ears with our hands, and opened our mouths as if preparing for an explosion to ensure legs wouldn’t be torn off and our ears wouldn’t rupture. I could smell cordite in the air. I loved the odor. To me, it smelled like excitement. This was Breakout, the beginning of Hell Week. Tweet, tweet. We low-crawled to the sound of the whistle. Tweet, tweet, tweet. We stood up. The whistle drills continued between the explosions and the chatter of machine guns. Each time the whistle blew twice I crawled toward the sound, the asphalt rubbing the skin off my knees and elbows. Of the three whistle sounds, I quickly learned to hate the double tweet more than a single or triple. Finally the whistle blew three times and we stood up. Instructor Blah stood on a platform, calmly speaking into the bullhorn. “Get in formation!” We hurried into a formation of boat crews. “On your backs! On your feet! On your stomachs!” The commands were too fast, nearly impossible to follow. “You people are not working together! Drop and push ’em out!” We did push-ups. “Give me a muster, Mr. Mark,” Instructor Blah said. The artillery simulators and machine guns filled the air with thunder. “Boat leaders report!” shouted our class officer, Mr. Mark. With the sounds of the shooting, artillery, and screaming, it was challenging for us to communicate. My boat crew and I counted off and reported to our boat leader. He and the other boat leaders reported to Mr. Mark. “All present, sir!” “Any day now, Mr. Mark,” Instructor Blah said. “All present…” Mr. Mark reported. Instructor Blah raised his eyebrows. “All present?” “Yes. All present, Instructor Blah.” “Drop!” Blah said in the megaphone. We all dropped to the push-up position. “You people have given me a false muster!” Instructor Blah’s voice kept the same monotone. “One of your men is missing!” Not moving from the push-up position, Mr. Mark said, “Boat leaders, give me a muster!” The explosions and machine gun fire became louder. Maintaining the pushup position, my boat leader walked on his hands to each of us to make sure all of us were present. One of the other boat crew leaders reported, “Seaman Nelson is missing, sir!” Mr. Mark reported, “Seaman Nelson is missing, Instructor Blah.” “First you told me, all present! Now you tell me, Seaman Nelson is missing! Which is it?” “Seaman Nelson is missing, sir!” Ensign Mark said. Three instructors brought out Seaman Nelson, took off his blindfold, gag, and plasticuffs. Seaman Nelson returned to his boat crew. “The instructors kidnapped me,” he said. In all the noise and confusion of Breakout, no one had noticed he’d been missing. Instructor Blah calmly said, “No SEAL has ever been kept as a prisoner of war. But you left Seaman Nelson behind, didn’t you? Push ’em out!” We did push-ups until our arms gave out. Then we did calisthenics. During the jumping jacks, the Senior Chief SEAL sprayed a water hose inches from my face, directly up my nose. I counted off as best I could. “One, two, three, one! One, two, three, two!” My words became more and more gargled, and I gagged a couple of times. I was happy to be out of the push-up position and delighted not to be doing whistle drills, but I hid my emotions. No pain, no joy. Eventually, Senior Chief became bored and moved on to harass someone else. Tweet. Prostrated body, crossed legs, covered ears, opened mouths. Tweet, tweet. Low-crawl. Tweet, tweet. Low-crawl. Our bloody knees and elbows dragged across the merciless blacktop. As we neared the beach, I sped up so I could crawl on the soft sand instead of the asphalt. When I realized where we were headed—the cold ocean—I slowed down, not in a hurry to get wet. I had to be careful not to go too slow and receive special attention from the instructors. Stay with the group. We moved farther and farther from the chaotic sounds of instructors shouting, machine guns shooting, and artillery shells exploding behind us. Most of the instructors had faded away, and only a handful remained. Hell Week had barely begun, and we already appeared ragged, like hunted animals scraping to survive. We crawled on our hands and knees until we eventually reached the water line. Instructor Blah held the megaphone up to his lips. “Prepare for surf torture!” “Hooyah!” we shouted in unison. I don’t know where the sudden burst of spirit came from, but it lifted us. We formed a line, facing the instructors, and we locked arms. “You have something that belongs to the instructors, and we want it back!” Instructor Blah said. At that moment, we were the proudest we’d ever been as a class. The instructors thought they could break us, but we believed they couldn’t. We were in control. We had something they wanted, and they weren’t going to get it. “Hooyah!” “Take three steps backwards and sit down!” “Hooyah!” Our voices shouted louder than ever. Arms locked, we sat down in frigid water up to our necks, but the water didn’t seem so cold. We were fighting back. “You give us the bell, and the instructors will take it easier on you! You don’t give us the bell, and this is going to be the worst Hell Week ever!” We remained defiant. “Hooyah!” Waves of water crashed over us. “You have stolen government property! That’s a federal offense!” The more Instructor Blah asked for the bell, the more our spirits shot into outer space. “Hooyah!” we called out, as if flipping our middle fingers. Some of us were laughing. “You will all end up in the brig if you don’t return our bell!” Sitting there in the water, my classmates and I responded by breaking out in song to the tune of “Take Me Out to the Ball Game.” Take me out to the surf zone, Take me out to the sea, Make me do push-ups and jumping jacks, I don’t care if I never get back, For it’s root, root, root for the SEAL Teams, If we don’t pass, it’s a shame, For it’s one, two, three rings you’re out Of the old BUD/S game! “Hooyah!” we shouted merrily. The instructors quietly conferred with one another as we sat in water up to our chests. Each successive wave hammered us, sapping the warmth from our bodies and push-pulling at our locked arms. Our butts scraped forward and back across broken seashells and rocks. We started to shiver, and our arms began to weaken. “If you quit now, you can have a blanket and a hot cup of cocoa…with marshmallows,” Instructor Blah said calmly in the megaphone. I retreated into my own private world of cold and pain. The hush among my classmates told me that they were doing the same. We shorter guys sat deeper in the water than the others. Petty Officer Lin, a Ranger veteran who’d fought in Grenada, who had completed half of Hell Week in an earlier class, shivered more than anyone. The waves began to break our human chain. Soon, most of us were separated. I knew this couldn’t go on forever. I knew the instructors had carefully calculated the air temperature, water temperature, and wind speed, so they knew the maximum amount of time they could expose us to the cold without killing us. Physically, I could survive this. I just had to endure the pain mentally. The instructors wanted their bell, and we weren’t going to give it to them. The battle of wills had only just begun... You can read the rest of my story here in Navy SEAL Training Class 144: My BUD/S Journal WARNING: Do not try any of the activities described here on your own. Even with the supervision and guidance of active-duty SEAL instructors, serious injuries have resulted. Without this experienced supervision and guidance, permanent injuries and death can result. Wearing only our UDT shorts, my class climbed the outside stairs to the top of the fifty-foot dive tower and entered. Inside, I lowered myself into the warm water. The depth was fifty feet. I would have to dive down about fifteen feet and tie five knots: becket bend (sheet bend), bowline, clove hitch, rolling hitch (1), and square knot. These included some of the knots we would have to use for demolitions. For example, the becket bend and square knot can be used for splicing the end of det (detonating) cord. I learned most of the knots in Boy Scouts, and we practiced these at BUD/S, so I had no problem doing them, but this was the first time tying them at 15 feet underwater. We could tie one knot for each of five dives, but I thought that five dives would be too tiring. Or one dive with five knots—I didn’t think I had the lungs for that. Or any combination we wanted. I greeted the instructor, who wore SCUBA gear. “Respectfully request to tie the becket bend, bowline, and clove hitch.” He gave me the thumb down. I mirrored his thumb down, showing him that I understood. He gave me the sign again, and I did my combat descent fifteen feet below, where I had to tie into a trunk line secured to the walls. In Boy Scouts, I could tie the bowline with one hand in the dark, so I was able to tie it fast using both hands and my eyes open. Still underwater, I tied the other two. Then I gave the instructor the OK sign. He checked the knots and gave me the OK sign. I untied them and gave him the thumbs up. He acknowledged, pointing his thumb up—giving me permission to ascend. On my second dive, I tied the last of the two knots and gave the instructor the OK sign. He didn’t even seem to look at the knots, staring into my eyes. I saw he was going to give me trouble. I gave him the thumb up sign to ascend, but he just kept staring. The depth put pressure on my chest, and my body craved air. I knew what the instructor was looking for, and I wouldn’t give him the satisfaction. The SEAL instructors had taught me well. I can ascend myself, or when I pass out you can drag my body to the surface. Either way. He smiled and gave me the up signal before I even came close to passing out. I wanted to shoot to the top, but I couldn’t show panic. And shooting to the top isn’t very tactical. I ascended as slow as I could. Pass. Not all of my classmates were as lucky, but they would get a second chance. Note: Thanks to C. for taking time after Hell Week to update me on the knots. Any errors are my own. (Photos of becket bend, bowline, and clove hitch courtesy of Markus Barlocher. Square knot photo courtesy of Ben Frantz Dale.) December 31, 1986, I arrived at the Naval Special Warfare Center in Coronado, California to begin BUD/S training. The place seemed to have died for the holidays, so I slipped in mostly unnoticed. I could've waited to report later, but I was too anxious. On Friday, January 2, 1987, SEAL Master Chief Rick Knepper helped my classmates and I off to a proper start. He looked like an ordinary guy in his forties, calmly leading us in calisthenics on the beach late in the afternoon—we grunted and groaned, but he didn’t seem to break a sweat. Some guys knew about his combat experience and some didn’t.

Rick Knepper served in Vietnam with SEAL Team One, Delta Platoon, 2nd Squad. Knepper’s squad thought they knew about Hon Toi, a large island in Nha Trang Bay. From a distance, the island looked like a big rock sitting in the ocean for birds to take a crap on. But two Viet Cong (VC), tired of fighting and being away from family, defected from the island—leaving a VC camp behind. Knepper’s squad of seven SEALs inserted into the island by boat under darkness—not even the moon shone. Never ones to take the easy way, 2nd Squad free-climbed a 350-foot cliff. After reaching the top, they lowered themselves into the VC camp. The seven-man squad split into two fire teams, taking off their boots and going barefoot to search for some high value targets (HVTs) to snatch. But the VC got the drop on Lieutenant (j.g.) Bob Kerrey’s fire team. A grenade landed at his feet and exploded, slamming him into the rocks and destroying the lower half of his leg. The lieutenant’s fire team fought back while he called in the other fire team, catching the VC in a deadly crossfire. One SEAL, a hospital corpsman, lost his eye. Four of the enemy tried to escape but the SEALs cut them down. Three VC stayed to fight—but didn’t live to fight again. One of the SEALs put a tourniquet on Lieutenant Kerrey’s leg. The squad snatched several VIPs along with three large bags of documents (some including a list of VC in the city), weapons, and other equipment. Lieutenant Kerrey continued to lead Rick Knepper and the others in his squad until they were evacuated. The intel they got from the documents and HVTs gave critical information to the allied forces in Vietnam. Lieutenant Bob Kerrey received the Medal of Honor and would later become a senator and governor of Nebraska. Although others still talk about that op, I never heard Master Chief Knepper talk about it or any other. He served as a mentor to my classmates and me. Without his taking us under his wing, we would’ve been left on our own until the rest of the guys arrived and our BUD/S class officially formed. And I was going to need all the help I could get. In a classroom at the Naval Special Warfare Center, Instructor Stoneclam stood next to a 13-foot long, black, rubber boat resting on the floor in front of my class.

“Today, I’m going to brief you on Surf Passage. This is the IBS. Some people call it the Itty-Bitty Ship, and you’ll probably have your own pet names to give it, but the Navy calls it the Inflatable Boat, Small. You will man it with six to eight men who are about the same height. These men will be your boat crew.” He drew a primitive picture on the board of the beach, ocean, and stickmen scattered around the IBS. He pointed to the stickmen scattered in the ocean. “This is you guys after a wave has just wiped you out.” He drew a stickman on the beach. “This is one of you after the ocean spit you out. And guess what? The next thing the ocean is going to spit out is the boat.” Instructor Stoneclam used his eraser like a boat. “But now the 170-pound IBS is full of water and weighs about as much as a small car. And it’s coming right at you here on the beach. What are you going to do? If you’re standing in the road, and a small car comes speeding at you, what are you going to do? Try to outrun it? Of course not. You’re going to get out of the road. Same thing when the boat comes speeding at you. You’re going to get out of the path it’s traveling. Run parallel to the beach. “Some of you look sleepy. All of you drop and push ‘em out!” Later, the sunshine dimmed as we stood by our boats facing the ocean. Bulky orange kapok life jackets covered our Battle Dress Uniforms (BDU’s). We tied our hats to the top button hole on our shirt collars with orange cord. Each of us held our paddles like rifles at the order-arms position, waiting for our boat leader to return from where the instructors briefed him and the other boat crew leaders. Our group was the “Smurf Crew”—the boat with the shortest men. Our boat leader quickly returned and gave us orders. With boat handle in one hand and paddle in the other hand, we raced with our boat into the water. The other boat crews raced too. “One’s in!” our boat leader called. Our two front men jumped into the boat and started paddling. I ran in water almost up to my knees. “Two’s in!” Martinez and I jumped in and started paddling. “Three’s in!” The third pair jumped in and paddled, followed by our boat leader, who used his oar at the stern to steer. “Stroke, stroke!” I dug my paddle in deep and pulled back as hard as I could. I glanced over at another boat where the Egyptian officer, had a big smile on his face like he was on the Catalina cruise. His paddle leisurely slapped the top of the water. In front of us, a seven-foot wave formed. “Dig, dig, dig!” Our boat climbed up the face of the wave. I saw one of the boats clear the tip. We weren’t so lucky. The wave picked us up and slammed us down, sandwiching us between our boat and the water. As the ocean swallowed us, I swallowed a mouthful of boots, paddles, and cold saltwater. Eventually, the ocean spit us onto the beach along with most of the other boat crews. The instructors greeted us by dropping us. With our boots on the boats, hands in the sand, and gravity against us, we did pushups. Then we gathered ourselves together and went at it again—with more motivation and better teamwork. This time, we cleared the breakers. Back on shore, a boyish-faced trainee from another boat crew, picked his paddle up off the beach. As he turned around to face the ocean, a boat raced toward him sideways. Instructor Stoneclam shouted in the megaphone, “GET OUT OF THERE!” Boy-Face ran away from the boat, just like the instructors told us not to. Fear has a way of turning Einsteins into amoebas. “RUN PARALLEL TO THE BEACH! RUN PARALLEL TO THE BEACH!” Boy-Face continued to try to outrun the speeding vehicle. The boat came out of the water and slid sideways like a hovercraft over the hard wet sand. When it ran out of hard wet sand, its momentum carried it over the soft dry sand until it hacked Boy-Face down. Instructor Stoneclam, other instructors, and the ambulance rushed to the wounded man. Doc, one of the SEAL instructors, started first aid. I never heard Boy-Face call out in pain. The boat broke both his legs at the thigh bones. When the day finished, we hit the hot showers, but Parsons, the punker with Billy Idol hair, grabbed his surfboard and headed back for more: “Those waves are thrashin’!” You can read the rest of my story in Navy SEAL Training Class 144: My BUD/S Journal. WARNING: Do not try any of the activities described here on your own. Even with the supervision and guidance of active-duty SEAL instructors, serious injuries have resulted. Without this experienced supervision and guidance, permanent injuries and death can result.

I’d always thought drowning is one of the worst ways to die. The sun lay buried in the horizon, as my class marched double-time through the Naval Amphibious Base at Coronado, California. Wearing the same camouflage uniforms, all of us sang out in cadence looking confident, but the song of our voices was hollow. Wake up, wake up, N.A.B. We’ve been up since half past three Runnin’, swimmin’ all day long That’s what makes a tadpole strong Whooyah hey, runnin’ day Whooyah hey, easy day Our anxieties manifested themselves as lingering mists from our warm breath hitting the winter air. The noise of our combat boots struck the black asphalt with melancholy. Most of the men in my Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL (BUD/S) class were about 21 years old—I was only 19. Together we were a smorgasbord of life: Egyptian army officer, MIT graduate, surfer punk, etc. Each of us had different reasons for becoming Navy SEALs: show patriotism, become king of the surfers, etc. But on that cool winter’s morning, we all had one thing in common: dread. We arrived at the pool located at Building 164 and stripped down to our UDT swim shorts. The SEAL instructors watched us with shark eyes. We grouped ourselves in pairs with our swim buddies. My swim buddy asked, “Do you want to go first or should I?” “I want to get this over with,” I said. We stood at the deep end of the pool. Goose bumps pricked our flesh as each of our partners tied us up with high strength cord. My partner tied my feet together. “Tie it good,” I said. “I don’t want to have to do this twice.” After finishing the knot, he proceeded to tie my hands behind my back. Stoneclam wore his khaki UDT (Underwater Demolition Team) shorts and a dark blue t-shirt. The t-shirt had a thin yellowish-gold border on the sleeves. Two cartoon-like figures were on the left breast: a frog holding a burning stick of dynamite in its hand and a seal carrying a knife in its mouth. Written in small, yellowish-gold letters were the words: UDT/SEAL Instructor. Kneeling down on one knee, he touched the water reverently as if to consecrate it for us. He climbed up to the lifeguard chair and took his ritualistic position. “You are all going to love this. Drown-proofing is one of my favorites. Sink or swim, sweet peas.” Half of my class stood at the edge of the deep end with our feet tied together and hands tied behind our backs. Our swim-buddies stood behind us. Instructors were joking, but it was all a peripheral blur to me. I can’t let them get inside my head. Focused on calming my respiration and heartbeat. Instructor Stoneclam said, “When I give the command, the bound men will hop into the deep end of the pool. You must bob up and down twenty times, float for five minutes, swim to the shallow end of the pool, turn around without touching the bottom, swim back to the deep end, do a forward and backward somersault underwater, and retrieve a face mask from the bottom of the pool. “If your ropes come undone, you must start over from the beginning. If your ropes come undone a second time, you fail. If you break your ropes, you pass—but don’t try it. I only know of one student who ever broke his ropes. We’ll be watching you to make sure no one cheats.” Standing on the edge of the pool, I should have realized how abnormal all this was. Just doing all that bobbing and swimming and somersaults without my hands and feet tied would be hard enough. My mind focused on how peaceful the water was. My breathing and heart rate slowed. Instructor Stoneclam’s dark eyes probed us. “First group, enter the water.” The smooth surface of the water broke as we jumped in. A flurry of thoughts assaulted me: panicking, suffocating, drowning. Block the negative. Be calm. Avoid the negative. The heated pool is warm. Focus on the warmth. Become one with the water. My classmates and rose and sank at different heights and depths. Some touched the bottom and were already rising to the surface. A negative thought wrestled with me: the guys at the top are going to breathe while I’m still down here. I waited helplessly for my feet to touch the bottom. Wait for the breath. Slow it down. Control the rhythm. I imagined soft ballet music. My toes touched the concrete bottom. Don’t shoot out of the water like a missile and draw the attention of the instructors. I gently pushed off. I wanted air, but I couldn’t think about it. My head cleared the surface. I heard screams and saw splashing on the other side of the pool. I closed my eyes and filled my ears with ballet music. My mouth formed a tight circle, sucking a bite of oxygen straight to my lungs. I sank slowly to the bottom. The instructors can’t touch me here. The water is my haven. Pushing off from the bottom again, I opened my eyes and continued to imagine ballet music as my classmates and I continued to rise and fall in our new haven. The Egyptian officer smiled, looking like a brown, oversized water lily. Priest, the surf-punk, made a goofy face at me and wiggled his body like some sort of wacky water worm as he rose upward. I smiled, bobbing up and down in the water wearing my pink tutu. On one of my trips to the surface, I looked over to the commotion at the other side of the pool. One of my classmates thrashed the water trying to get to the edge of the pool. “Help me, I’m drowning! Ahggh!” Instructor Stoneclam used the lifesaving pole to push him away from the edge, “If you were drowning, you wouldn’t be telling me about it.” The panicked guy bit the pole. I got my bite of air and sank down. When I came back up, the panicked student was being helped out of the pool—he had enough of training. After bobbing, I floated for five minutes. Next, I began my dolphin kick along the length of the pool. Keep it slow. Keep the rhythm. I kicked then turned my head to breathe—side-stroke style. Kick-and-breathe, kick-and-breathe. I reached the shallow end of the pool and began making a dolphin-turn right. Parsons was turning left, aimed for a head-on collision course with me. If either of us touched the bottom of the pool, we’d fail. I became anxious and started to lose my rhythm. Parsons dove underneath me as we made our turn. Our bodies scraped each other, but neither of us touched the bottom of the pool. I became more anxious. I dolphined my way back to the deep end. There I bobbed once. I did my forward somersault. I still hadn’t recovered my breathing rhythm after the near-collision with Priest. Most of my classmates had already finished their forward and backward somersaults. Nineteen face masks lay on the bottom of the pool. One-by-one the masks disappeared as each of my buddies grabbed a mask with their teeth and rose to the surface, completing their job. I was the last one in the pool. I could feel Instructor Stoneclam’s eyes on me. I did the backward somersault. My breathing and movement became uncoordinated. The threat of failure attacked me. My chlorine-saturated eyes frantically searched the blurry bottom for a face mask. I spotted one mask on the bottom at the far end of the pool. I can’t make it that far. Suddenly, my blurred vision caught sight of a mask down to my left. My feet touched the bottom—my toes only inches away. I dropped to my knees. I tried to lean over to grab the mask with my teeth. But I had swallowed too much air during my somersaults, and my body floated up before I could bite the mask. My body stopped halfway up. There was no air in my lungs to float me to the top and too much air in my stomach to allow me to sink to the bottom. The taste of chlorine made me want to vomit. Fear stepped aside to let discouragement make its entrance. Discouragement was infinitely more powerful than fear. I felt myself shrinking. I heard voices—my classmates cheering me on. They seemed so far away. I was too weak. I failed. Discouragement smashed me, destroying every particle of human energy from me. The hammer of discouragement rose high in the air, preparing to make its final blow. But I didn’t want it to end this way. I didn’t want to fail. I started to get angry. Angry at fear and discouragement. Angry at Instructor Stoneclam. Angry at anything that would get in my way from succeeding—including myself. My spirit exploded. Its heat and power rumbled through me. The shockwave overwhelmed my senses. My feet kicked rapidly, propelling me upward. I surfaced with half of my body shooting out of the water. I flipped like an angry fish and dove head first into the water, frantically kicking my tied feet. I shot down at the mask, and my forehead smashed into the floor, stopping me. I twisted my head around and clenched the black strap with my teeth. I kicked and wiggled without oxygen, managing to move head-first toward the top. My head felt so dizzy. Complete the mission. I struggled halfway to the surface. My body was heavy. My peripheral vision became grey. I kicked harder. Every part of me craved oxygen as the grey circle around my vision became smaller, darker. My body started to tingle. I felt like I was losing consciousness--getting harder and harder to focus on anything. I managed to poke my head out of the water. Madly, my feet kept kicking. Some classmates started to applaud. “Shut up!” Instructor Stoneclam barked. I refused to stop kicking unless Stoneclam told my swim buddy to help me out, and I refused to let go of the mask. Instructor Stoneclam studied me leisurely. I sucked air and water through my teeth. I figured he could either let my buddy help me out from the pool, or Stoneclam could rescue me when I became unconscious and sank to the bottom. Either way, I wasn’t going to let go of the mask. Instructor Stoneclam told my swim buddy, “Pull him out.” I felt incredible relief as my partner and another student pulled me out. The ground felt strange, and I had to sit down because my legs didn’t support me well. My classmates untied my hands. I felt like a fish, not knowing what to do with my hands except flap the kinks out of my wrists. My head ached. Steam rolled off my wet body. An instructor told me, “I’ve never seen anyone pull their mask out like that. You’ll have to explain your technique.” The other instructors smiled. Instructor Stoneclam barked, “Next!” I helped tie my swim buddy’s feet and hands. “Second group, enter the water,” Instructor Stoneclam said. I no longer thought drowning was one of the worst ways to die. Drownproofing replaced my old fear with a new one: failure without trying everything I can do to succeed. You can read the rest of my story in Navy SEAL Training Class 144: My BUD/S Journal. When Class 143 finally began BUD/S Indoctrination (Indoc) I found out that we would be taking the physical screen test again. I nearly panicked hearing that those who failed would be dropped on the spot. But the fear must’ve motivated me because I passed while others were sent packing. From that point on, it took everything I had to get through the calisthenics of Indoc without being targeted by the instructors for not keeping up. During the pool swims, I always finished dead last. Guys already started to ring the bell—quitting. The beach runs hammered me. Soft sand sucked the energy out of my legs, but waves assaulted me on the hard packed sand. Some guys dropped way behind and others stayed in front with the group. I ran with the guys strung out in the middle. One day, Instructor Benelli ran alongside me. “Do you want to fall behind with the guys walking in the back or keep up with the guys running in front?” I gasped. “Front.” “Run with your thighs and not your lower legs, then. Just pick up your thighs and put them down. Keep your arms loose, so you don’t waste energy. And breathe.” I followed his advice and somehow managed to make my way forward. My former shipmate, Rudy, stayed strong like Clint Eastwood and was almost always up front, giving me someone to catch up to. Other guys, like Howard E. Wasdin, who I met and became friends with in Indoc, fell behind on one run and received personal attention from the instructors while the rest of us hit the showers. In Howard’s case, he never made that mistake again. In contrast, Claude seemed to fall farther behind on every run. I couldn’t understand why. Claude and I had run together before BUD/S, and he’d never had trouble before. But I noticed he didn’t smile anymore. One day he rang the bell, and I never saw him again. After one particularly tough day of training, Howard walked around the barracks asking, “Who wants to go with me for a run on the beach?” I thought he was nuts. “You’re in BUD/S. Isn’t that enough?” What seemed even nuttier to me was that some of the guys actually went. Eventually, even Howard had enough, though, so we’d take care of personal business and have fun on Saturdays, and we'd go to church on Sundays. And so it went. Howard set a positive example for me in BUD/S and was a great friend to me. But when I injured a leg muscle trying to swim with my hands and feet tied while preparing for “drownproofing,” that was the end of our training together. The doctors pulled me out of Class 143. The bad news was that I had to start Indoc all over from the very beginning. But the good news was that I was still in the game. I’d gotten a taste of BUD/S, and I was determined to hook up with Class 144 and kick some ass. You can read the rest of my story in Navy SEAL Training Class 144: My BUD/S Journal. Note: Years later, in 1993, in Mogadishu, Somalia, Howard and three other snipers from SEAL Team Six, along with Delta and others, snatched some of warlord Mohamed Aidid’s top cadre. Aidid’s militia used rocket propelled grenades to shoot down two Black Hawk helicopters. Howard and his buddies fought a hellish battle to get out of the city.

The rest of Howard’s story appears in SEAL Team Six: Memoirs of an Elite Navy SEAL Sniper. |

the pages turn themselves...To get your copy of From Russia without Love, you just need to tell me where to send it. Stephen Templin

Steve is a NYT & international bestselling author. And dark chocolate thief. Categories

All

|